In my previous post, I introduced the idea of L-systems and how I used them to generate foliage procedurally. I quickly ran into performance issues, which I was able to address somewhat with frustum culling. In this post, I’ll explain how I further optimized the scene by using DirectX 12’s new mesh shader pipeline. I’ll also touch on my use of a Z-prepass, which mitigated some overdraw issues, especially with a large number of trees and leaves.

Vertex shader instancing bottleneck

Let’s first understand the problem with the vertex shader instancing pipeline. The vertex shader suffers from a long scoreboard stall which I documented in the previous post:

A long scoreboard stall

This means that the warp is stalled trying to read the instance data from memory. What can we do to mitigate this? Well, one observation we can make is that the instance data is being read multiple times per leaf. This is because the vertex shader is invoked once per vertex per instance. Each leaf has 8 vertices (4 each for the front and back faces), meaning that the instance data is being read 8 times per leaf. Cutting this down to once per leaf would likely get rid of this issue and this is where mesh shaders come in.

Finer control with mesh shaders

Mesh shaders are a new alternative to the geometry stages of the rendering pipeline, and can be thought of as compute shaders that can emit geometry. I won’t explain them in elaborate detail, but for more information, Shawn Hargreaves’ introduction and Erik Jansson’s GPU-driven rendering presentation are both excellent resources.

The new mesh shader pipeline (from here)

Mesh shaders bypass the Input Assembler stage and can read geometry data straight from buffers instead, or even generate it on the fly. They can also choose not to emit geometry at all, making it possible to easily perform culling on the GPU.

In my case, since the leaf geometry is small (a single quad per leaf), I emitted it entirely from a mesh shader without the need for a vertex or index buffer. I can also determine whether the leaf is front or back facing in the mesh shader and generate normals and texture coordinates accordingly (effectively performing backface culling myself), allowing me to cut the number of vertices per leaf down to 4. The mesh shader reads from the instance StructuredBuffer directly. Similar to compute shaders, mesh shaders have access to the SV_GroupIndex and SV_GroupID semantics and I used these to ensure that all threads in a thread group read from the StructuredBuffer in a spatially local manner.

I can also process more than one vertex per thread if I want. Since each instance has only 4 vertices and 2 triangles, I chose to process one instance per thread, instead of one vertex per thread as is the case with vertex shaders. This results in an eightfold reduction in the number of reads from the instance data StructuredBuffer compared to the vertex shader implementation.

The benefits don’t end there, though. I can also perform frustum culling in the mesh shader by generating a bounding sphere for the leaf and testing it against the camera’s frustum planes.

GPU frustum culling the leaves

For reference, the key parts of the mesh shader are given below. The complete code is available here. I later added some very simple animation as well, which I’ve omitted below.

// ...

typedef float4 BoundingSphere;

// The bounding sphere is expected to be the correct size and in world space

bool IsVisible(BoundingSphere bs, float4 planes[6])

{

float3 center = bs.xyz;

float radius = bs.w;

for (int i = 0; i < 6; ++i)

{

if (dot(float4(center, 1), planes[i]) < -radius)

{

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

// ...

struct InstanceData

{

float4 LocalPositionWithPad;

Quaternion RotationQuat;

float4 TexcoordUAndVRange;

};

// Contains leaf instance data

StructuredBuffer<InstanceData> Instances : register(t0, space0);

// ...

#define NUM_THREADS 32

#define VERTS_PER_INSTANCE 4

#define TRIS_PER_INSTANCE 2

static const float PI = 3.14159265359;

// 1 instance per thread!

[numthreads(NUM_THREADS, 1, 1)]

[outputtopology("triangle")]

void Billboard_MS(

in uint gtid : SV_GroupIndex,

in uint3 gid : SV_GroupID,

out indices uint3 tris[NUM_THREADS * TRIS_PER_INSTANCE],

out vertices VertexType verts[NUM_THREADS * VERTS_PER_INSTANCE])

{

// ...

// Compute the index for this thread

uint localInstanceIndex = gtid;

uint instanceIndex = gid.x * instancesPerGroup + localInstanceIndex;

VertexType outputVerts[vertsPerInstance];

uint3 outputTris[trianglesPerInstance];

bool visible = true;

if (instanceIndex < g_numInstances)

{

// Index into the instance buffer

InstanceData instance = Instances[instanceIndex];

// ... compute animation

// Get transform and determine if we're front-facing

instanceTransform._41_42_43 = instance.LocalPositionWithPad.xyz;

float4x4 worldMatrix = mul(mul(animationTransform, instanceTransform), g_parentWorldMatrix);

BoundingSphere bs;

bs.xyz = mul(float4(0, 0, 0, 1), worldMatrix).xyz;

// Radius is the length of the diagonal

bs.w = length(float3(g_cardWidth, 0, g_cardHeight));

visible = IsVisible(bs, g_cullingFrustumPlanes);

if (visible)

{

float3 rotatedFrontNormal = mul(float4(0, 1, 0, 0), worldMatrix).xyz;

bool frontFacing = g_useCameraDirectionForCulling ?

dot(rotatedFrontNormal, g_cameraDirection) < 0.f :

dot(rotatedFrontNormal, worldMatrix._41_42_43 - g_cameraPosition) < 0.f;

if (frontFacing)

{

// ... emit vertices and indices

}

else

{

// ... emit back-facing vertices and indices

}

}

}

else

{

visible = false;

}

// Set the output count based on the visible instances

// This must be called by every thread, even if its

// instance is culled

uint numInstancesEmitted = WaveActiveCountBits(visible);

SetMeshOutputCounts(vertsPerInstance * numInstancesEmitted,

trianglesPerInstance * numInstancesEmitted);

if (visible && instanceIndex < g_numInstances)

{

// Copy the data to the correct output index

uint index = WavePrefixCountBits(visible);

for (int i = 0; i < vertsPerInstance; i++)

{

verts[index * vertsPerInstance + i] = outputVerts[i];

}

for (int j = 0; j < trianglesPerInstance; j++)

{

// Indices need to be offset by the vertices

// emitted before

tris[index * trianglesPerInstance + j] = outputTris[j] + (vertsPerInstance * uint3(index, index, index));

}

}

}

Results

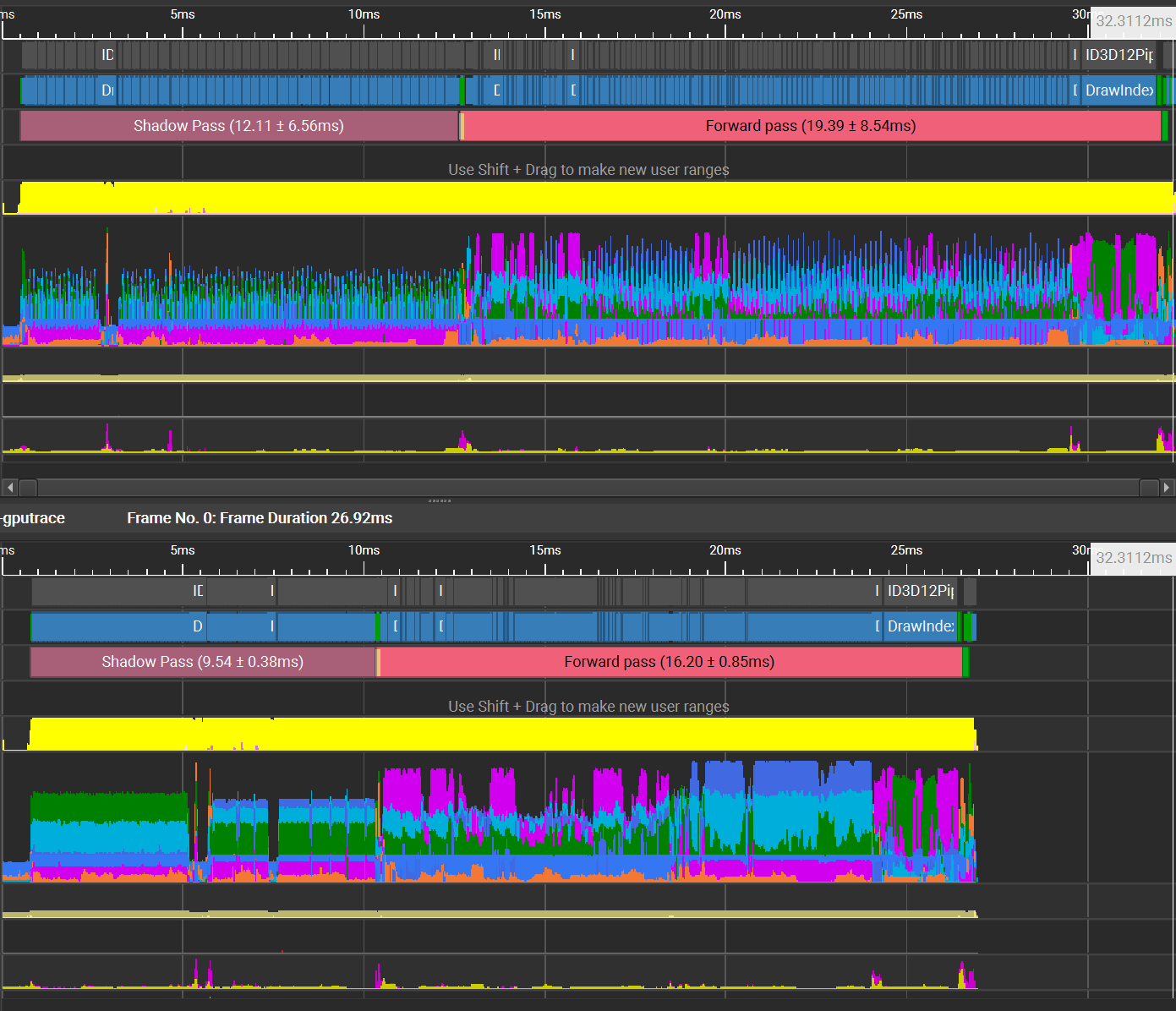

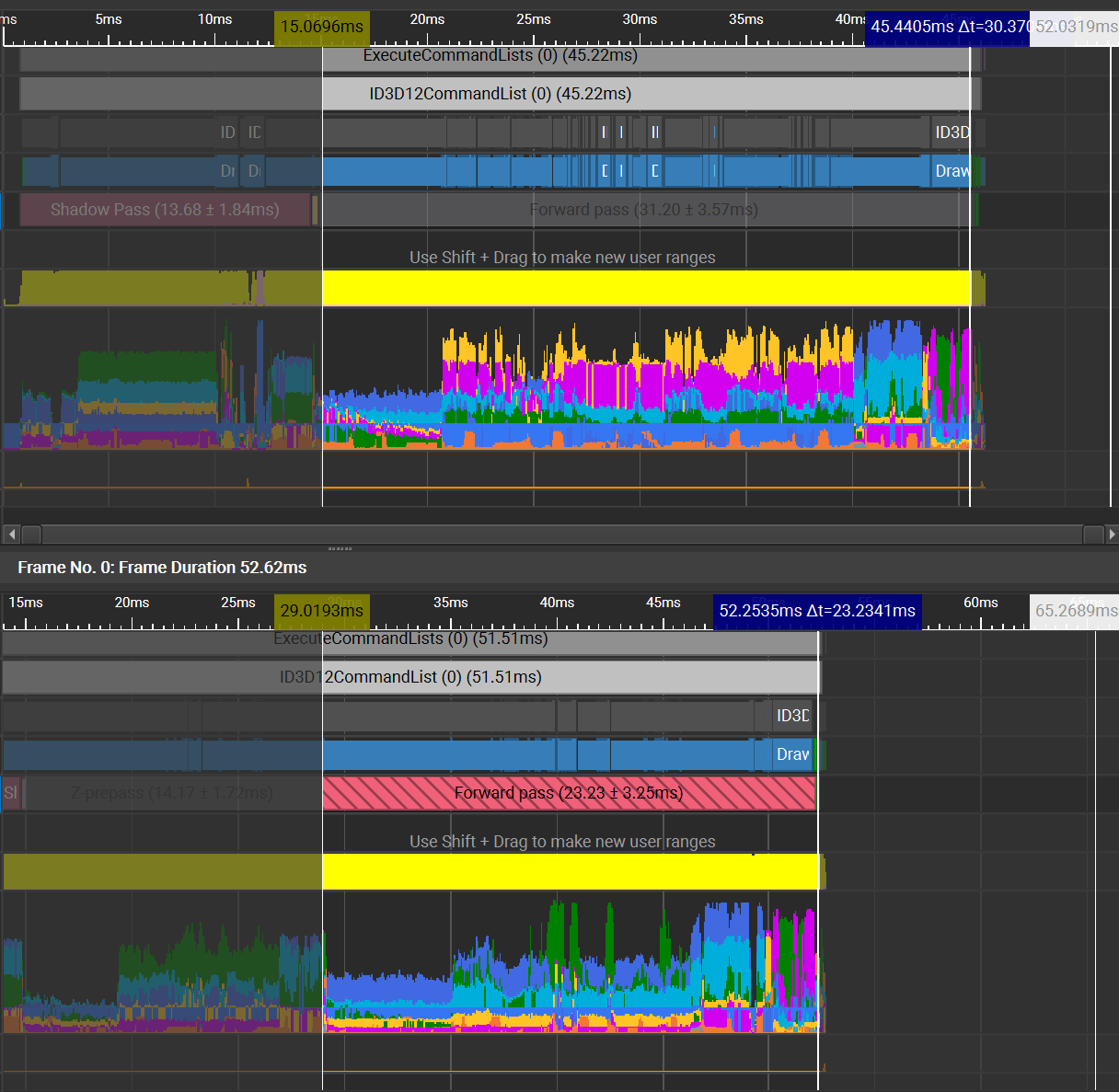

Vertex shader (top) vs mesh shader (bottom)

The mesh shader implementation has produced a substantial performance improvement. The throughput graphs also look less spiky, this is because in the mesh shader implementation I’m drawing all the objects that use the mesh shader pipeline in one batch. The branches and tree trunks still use the conventional vertex shader pipeline.

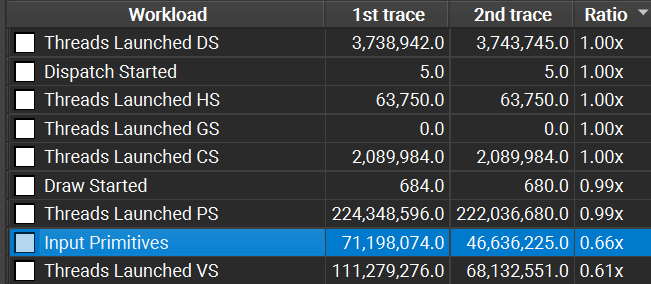

The mesh shader implementation draws fewer triangles

The input primitives are considerably lower in the mesh shader implementation (2nd trace). This is thanks to the backface culling and frustum culling. The majority of perf gains can probably be attributed to this.

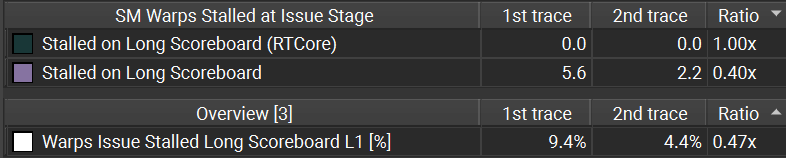

Long scoreboard stalls

Long scoreboard stalls have reduced, which is of course the intended effect.

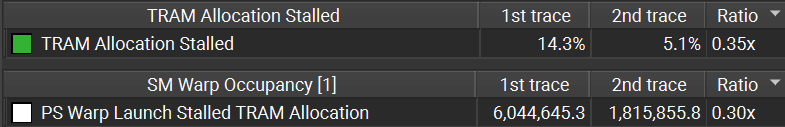

Triangle RAM allocation

Triangle RAM allocation (used to hold pixel shader attributes) has reduced in the mesh shader implementation, likely thanks to the reduction in input primitives.

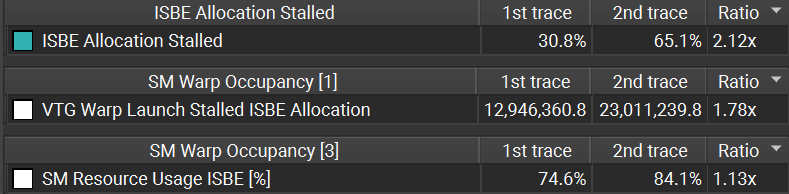

ISBE allocation

Stalls due to ISBE allocation have increased in the mesh shader implementation. ISBE memory is used to hold vertex attribute data such as normals and texture coordinates.

Z-prepass

Emboldened by these performance improvements, I filled the rest of the island with trees. There’s one more performance problem that I touched on in the previous post though: overdraw.

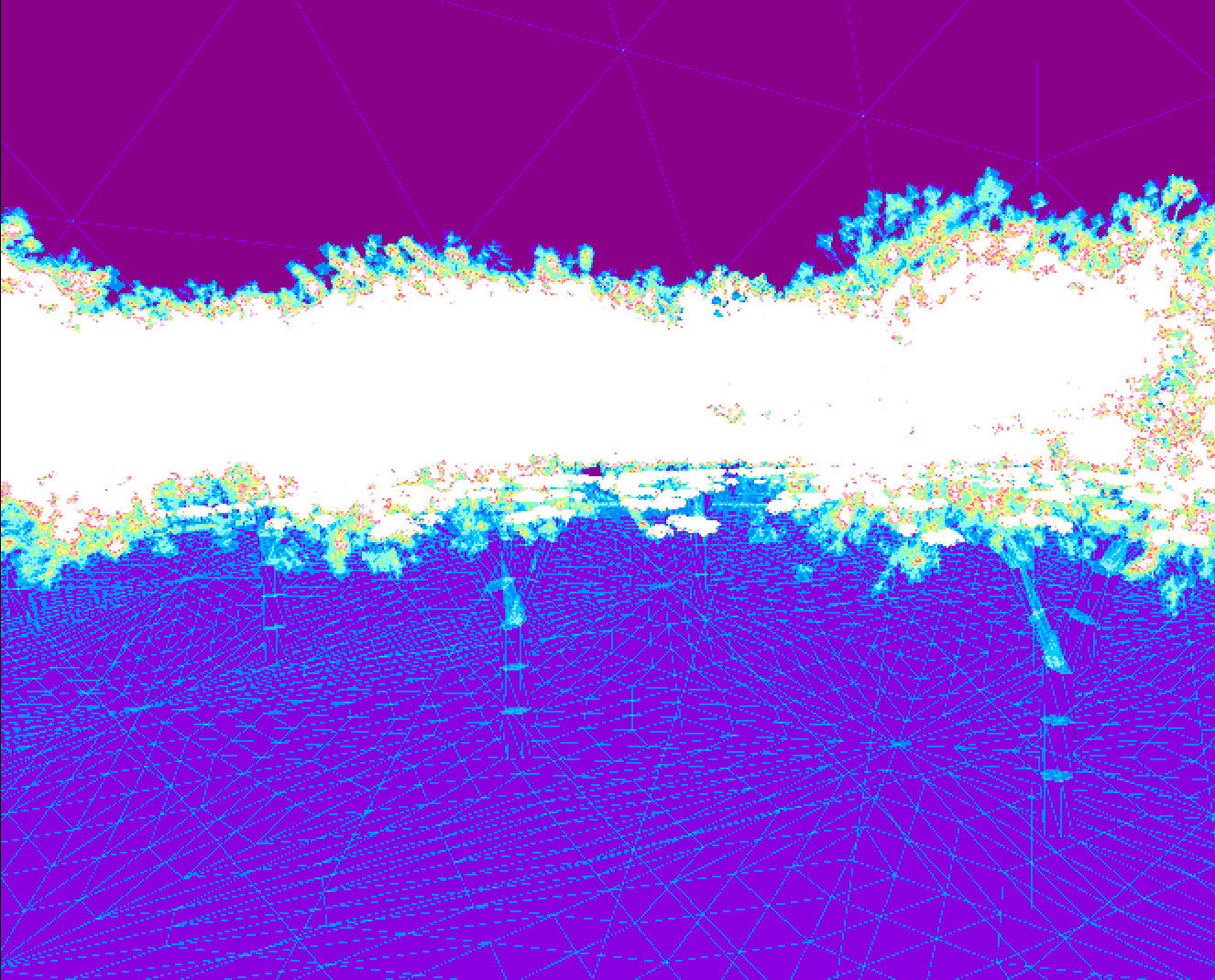

Quad overdraw, as visualised in RenderDoc

Overdraw occurs when objects closer to the camera are drawn after objects that are further away. Since the objects closer to the camera must occlude the other objects, the contents of the render target are overwritten with their pixels, and this results in the pixel shader being invoked multiple times for a given pixel. In my scene, the overdraw is obviously caused by the huge number of (often overlapping) leaves and branches.

I used a z-prepass to mitigate overdraw. A z-prepass is a pass in which the scene is either partially or fully drawn to the depth buffer only without a pixel shader bound. The scene is then drawn again with the pixel shader bound. Since the depth buffer is already seeded with data, the pixel shader shouldn’t be invoked more than once. Although this is effective in mitigating overdraw, one has to balance the cost of drawing the geometry twice. In my case, I drew only the leaves and branches as a part of the z-prepass, since those were the biggest overdraw offenders. In the forward pass, I disabled depth writes for geometry that had already been drawn in the z-prepass, and otherwise drew everything as normal.

The Z-prepass makes the forward pass cheaper

Unfortunately nSight’s overhead has made the z-prepass frame appear slower than the frame without the z-prepass, but when running the application normally, I observe a 3.5ms reduction in frame time thanks to the z-prepass. In the trace above, we can see that the forward pass has been made much cheaper.

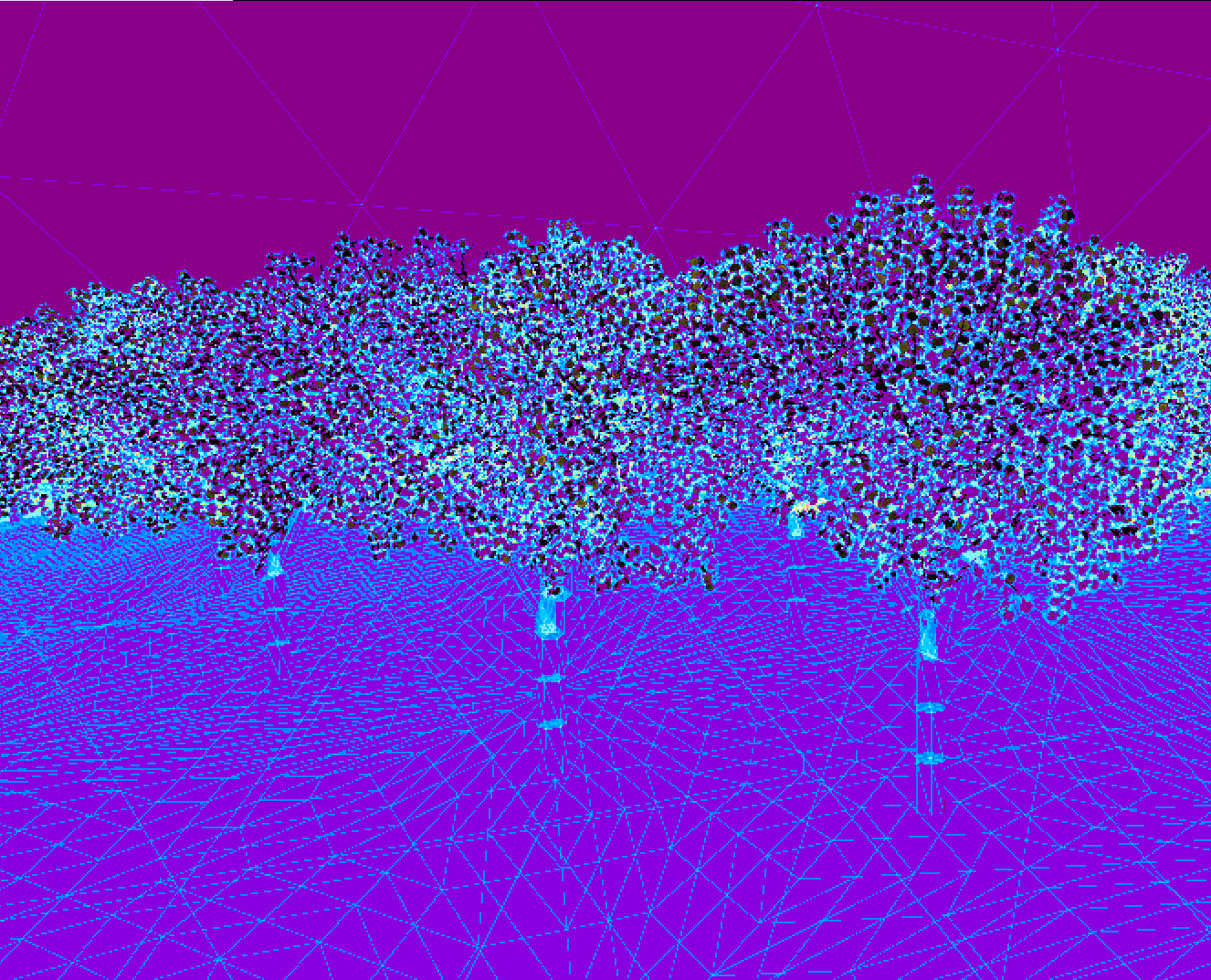

Quad overdraw with a z-prepass

As shown above, the z-prepass does indeed mitigate quad overdraw considerably.

Conclusion

In conclusion - I was able to use mesh shaders to draw leaves as alpha tested quads. They allowed me to minimise reads from the instance buffer and cut down on the submitted triangle count by performing various types of culling. In the future, I’d like to try drawing the rest of my geometry using mesh shaders as well by converting them to meshlets. There’s also the opportunity to perform occlusion culling in the mesh shader to reduce the number of submitted triangles even further. I think this technique of emitting quads from a mesh shader has the potential to be useful for rendering particles as well.