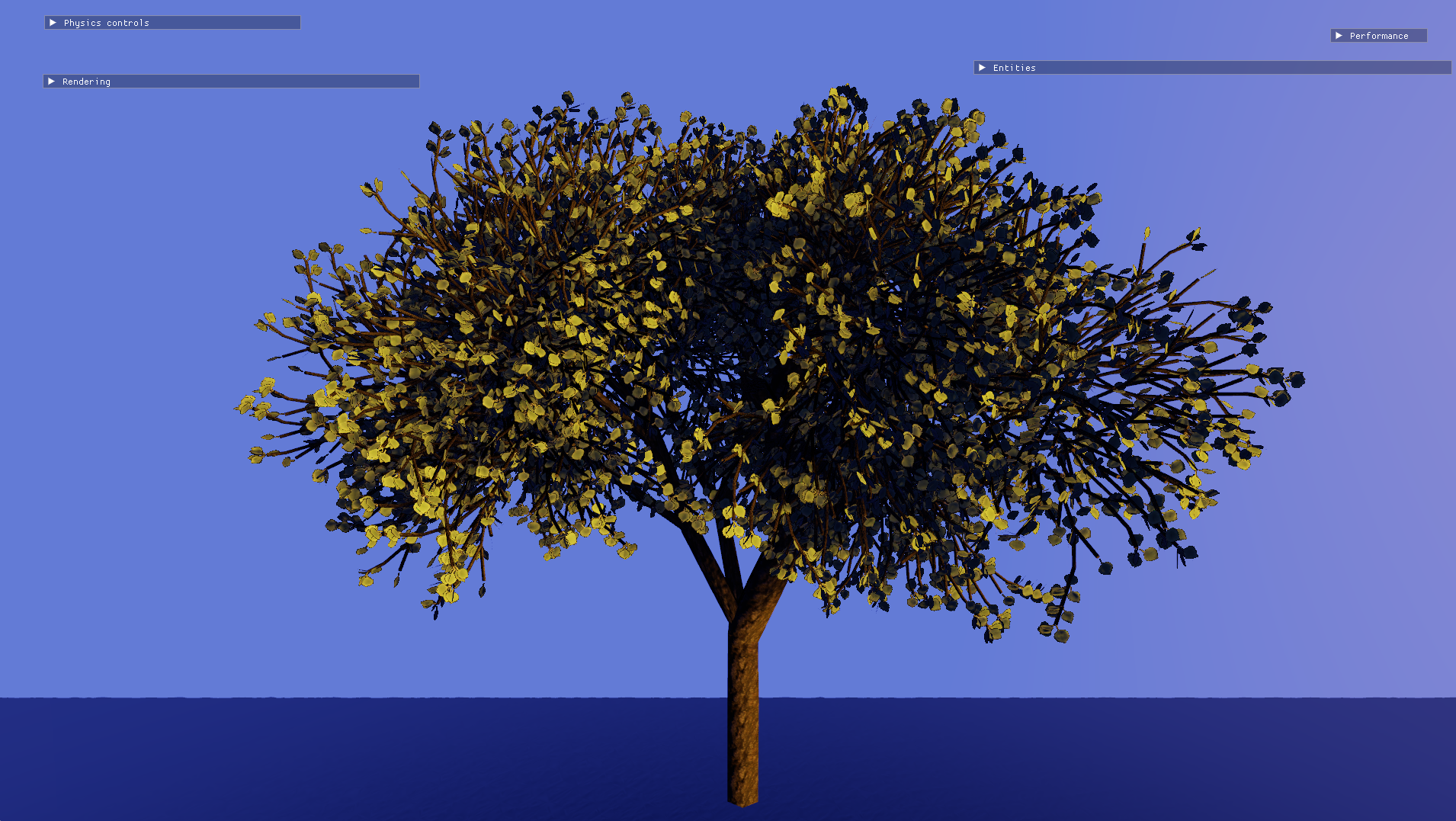

Procedurally generated bushes and trees are the latest addition to my engine. Although I used pre-made textures for the bark and leaves, the geometry for the trunk is generated entirely through code and each leaf is drawn separately through GPU instancing. This scene has some of the largest numbers I’ve ever had to deal with in any application: each tree has 467,856 triangles making up the trunk and branches and it comes with 30,600 leaves made of 4 triangles each. There are 101 trees in the scene, which adds up to 59,615,856 triangles for just the trees and nothing else! At 1080p on my RTX 4070 laptop GPU, this runs at around 39fps (25.64 msPF) when looking at all trees from a bird’s eye view, 54-70fps in the middle of the forest (18.52-14 msPF) and over 425fps when no trees are on screen (2.33 msPF). Although there’s still a lot of room for optimization here, I’ve made use of a combination of geometry instancing and culling techniques to try to ensure that my poor GPU isn’t force-fed all of these triangles at once. Here’s how I did it.

Building the foliage

L-systems

In their book The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants, Aristid Lindenmayer and Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz describe a means of modelling plant growth using a formal grammar called an L-system. An L-system consists of a set of production rules mapping a symbol to another string, as well as an ‘axiom’ symbol or rule which is used as a starting point. This is best illustrated with an example:

A plant-like structure generated from an L-system using this tool

This was generated with a starting axiom of X and the following set of rules:

X=F[+X]F[-X]+X

F=FF

To expand an L-system, symbols in the string are replaced according to their production rules, starting from the axiom. This is done for a configurable number of iterations n (7 in the above case), or generations.

To actually draw a generated string, it must be interpreted by a turtle, similar to the way a Logo turtle works. The symbols in an L-system represent commands to be followed by a turtle:

F: Move forward a step of some configured lengthd.+: Turn (yaw) left by some configured angle \(\delta\).-: Turn (yaw) right by \(\delta\).[: Begin a branch (push the turtle’s state onto a stack).]: End the current branch (pop and restore the turtle’s state from the stack).

In order to work in 3D space, some more symbols are necessary:

&: Pitch down by \(\delta\).^: Pitch up by \(\delta\).\: Roll left by \(\delta\)./: Roll right by \(\delta\).

I added one special symbol of my own:

L: This records a transformation matrix based on the current position and orientation of the turtle. These can later be used as attachment points for branches or leaves.

The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants goes on to describe more complex notations involving parameterized and stochastic productions, but the system described so far was sufficient for my purposes.

Topologizing an L-system

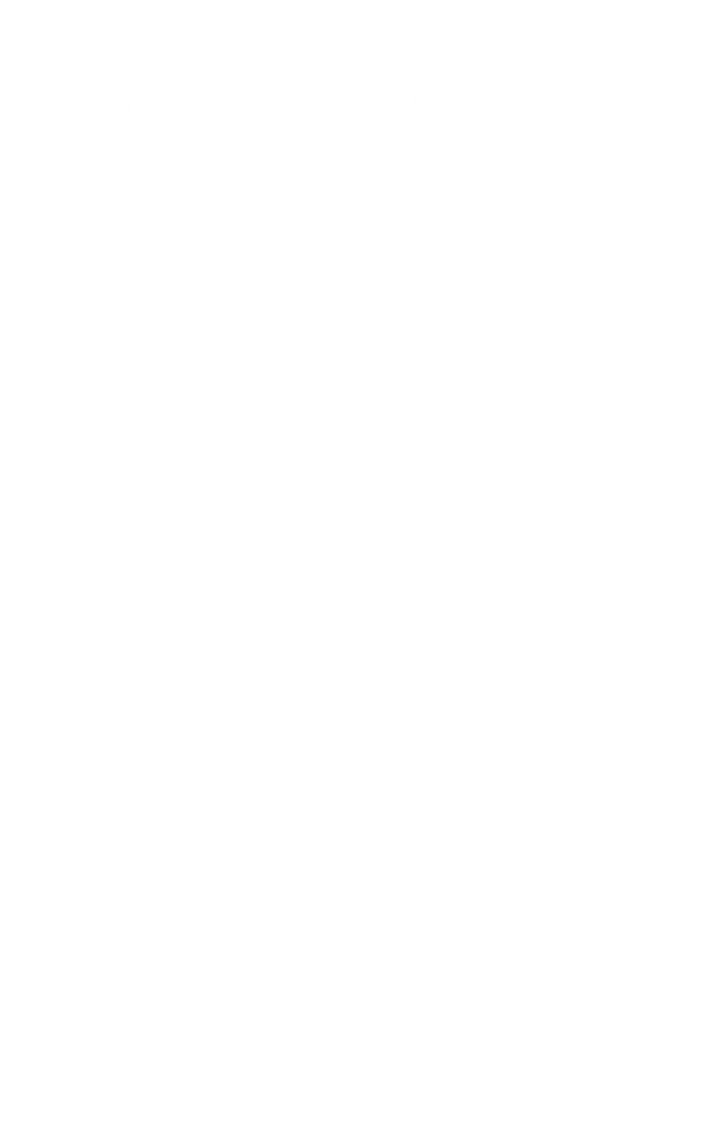

Of course, I need the turtle to generate a triangle mesh, not a stick structure. I decided to compose the generated structure out of 3D parts that are best described as conical frustums with angled tops.

An example part used to interpret an L-system

The top and bottom radius and the position and orientation of the top cap are all configurable, so the part can model anything from a cylinder to strange pipe or funnel-like shapes. It’s important to be able to make the top angled, as that allows parts to connect to each other at an angle without visible gaps or cracks.

I’m now ready to write the interpreter. Here’s what my turtle state looks like:

struct TurtleState

{

Vector3 Location = { 0, 0, 0 };

Quaternion ForwardRotation = Quaternion::Identity;

Quaternion UpRotation = Quaternion::Identity;

float Radius = 0.3f;

float RadiusFactor = 0.7f;

float AngleDegrees = 25.7f;

float MoveDistance = 1.f;

// ...

};

Radius, RadiusFactor, AngleDegrees and MoveDistance can all be passed through as configuration. Here, RadiusFactor is used to scale the Radius whenever a new branch begins. This provides a rudimentary form of tapering and prevents the branches from all being as wide as the trunk. The interpretation logic isn’t all that complex: the turtle munches through the expanded symbols, adjusting its state, emitting a part after consuming an F and generating an attachment transform whenever it consumes an L. Some care must be taken to ensure that the orientation of the top of a part matches the orientation of the subsequent part, but that’s about it!

Rendering a bush

I can now try and generate some plants. I configured and built an L-system as follows:

StartingRadius = 0.01

RadiusFactor = 1

AngleDegrees = 25.7

MoveDistance = 0.05

StartingRule = T

Generations = 6

Rules:

T=FFFX

X=F[/+FB[--L]][////+FB[++L]]/////////+FB[-L]

B=FF[/+FB[-L-L]][////+F[+L+L]B[+L+L]]/////////+F[+L+L]B

L=+^L/&--L/&&+L

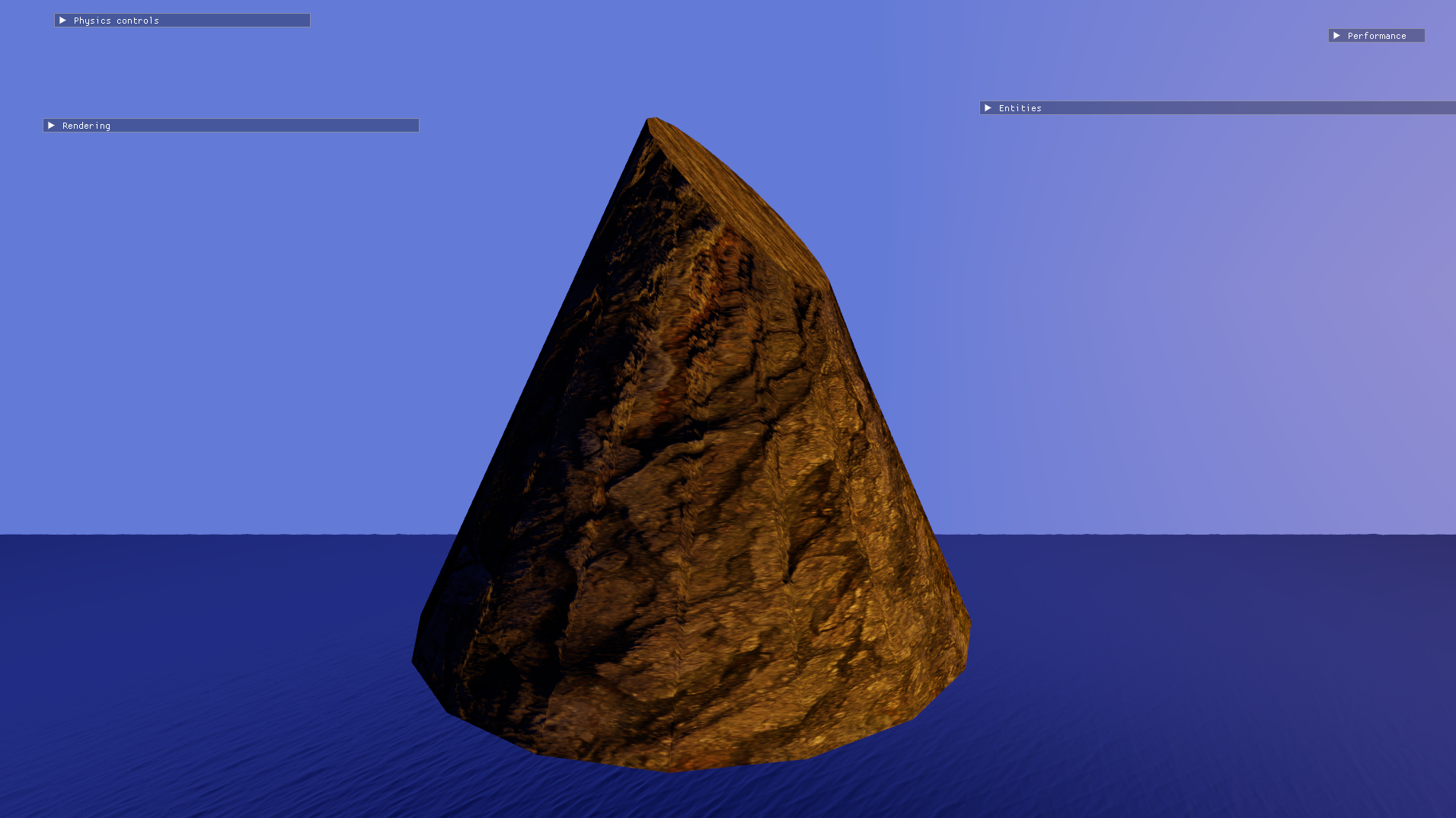

A bush without leaves

I’d say that looks pretty good! The ends of the branches are a bit stubby, and some of the branches are clipping into each other. I could tweak the L-system to fix this, but I didn’t bother since most of it would be covered up by the leaves anyway.

Drawing leaves with instancing

This little bush has 2,835 leaves. Issuing individual draw calls for one leaf at a time would be prohibitively expensive, so I submitted all the draw calls at once using DirectX’s geometry instancing.

I collected the generated attachment points from the L-system and wrote them into a StructuredBuffer, along with some sub-UV information for indexing into the texture atlas of the leaf. In my vertex shader, I can then index into this buffer using the instance ID, which DirectX provides as the SV_InstanceID semantic.

struct InstanceData

{

float4x4 WorldMatrix;

float2 TexcoordURange;

float2 TexcoordVRange;

};

StructuredBuffer<InstanceData> Instances : register(t0, space0);

// ...

OutputType main(InputType input, uint InstanceID : SV_InstanceID)

{

OutputType output;

float4x4 worldMatrix = mul(Instances[InstanceID].WorldMatrix, g_parentWorldMatrix);

// ...

I can then bind this StructuredBuffer to my root signature (I’m on DX12, but I’m not using bindless just yet, sadly) and draw all 2,835 leaves at once with a single DrawIndexedInstanced call.

Leaves!

I should make it clear that this approach of instancing every leaf isn’t a practical approach for production use, especially in titles that have to support older hardware - games mostly use 2D cards to represent entire branches rather than drawing one leaf at a time. But I decided to go down this route since I couldn’t be bothered finding or making a nice branch texture, and besides, this is more fun anyway.

Rendering a tree

How about something a bit bigger? I can use another L-system to generate a tree-trunk.

StartingRadius = 0.3

RadiusFactor = 0.5

AngleDegrees = 25.7

MoveDistance = 1

StartingRule = T

Generations = 3

Rules:

T=FFF[/+FX[--G]][////+FX[++G]]/////////+FX[-G]

X=F[/+FX[--G]][////+FX[++G]]/////////+FX[-G]

G=[//--L][//---L][\^++L][\\&&++L]

L=L///+^L

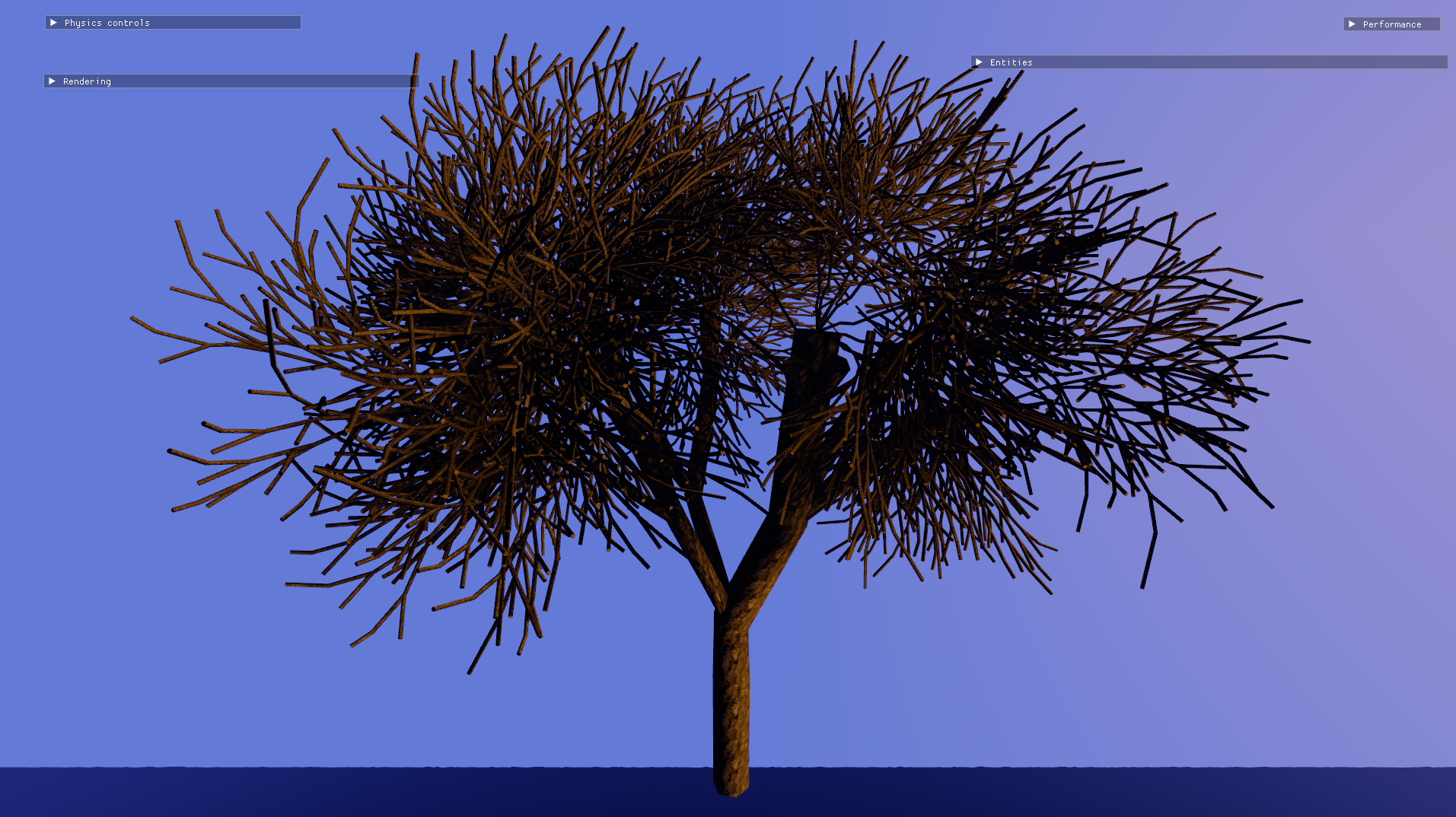

A tree trunk without leaves

I’m not sure if just adding leaves to this trunk will look quite as good this time, since some of the branches are thicker than others. This is because when the turtle starts a new branch, only the radius of the new branch is reduced, while that of the trunk is kept the same. Rather than add features to the interpreter to mitigate this, I decided to work around it using the system I already had. I used a separate L-system to model a branch of a tree.

StartingRadius = 0.02

RadiusFactor = 1

AngleDegrees = 20

MoveDistance = 0.2

StartingRule = X

Generations = 5

Rules:

X=FF/-F+F[--B]//F[^^B]//-FB

B=F[//^^B]F[\\&L]G[+B]-BG

G=F[//--L][//---L][\^++L][\\&&++L][\\&&+++L]

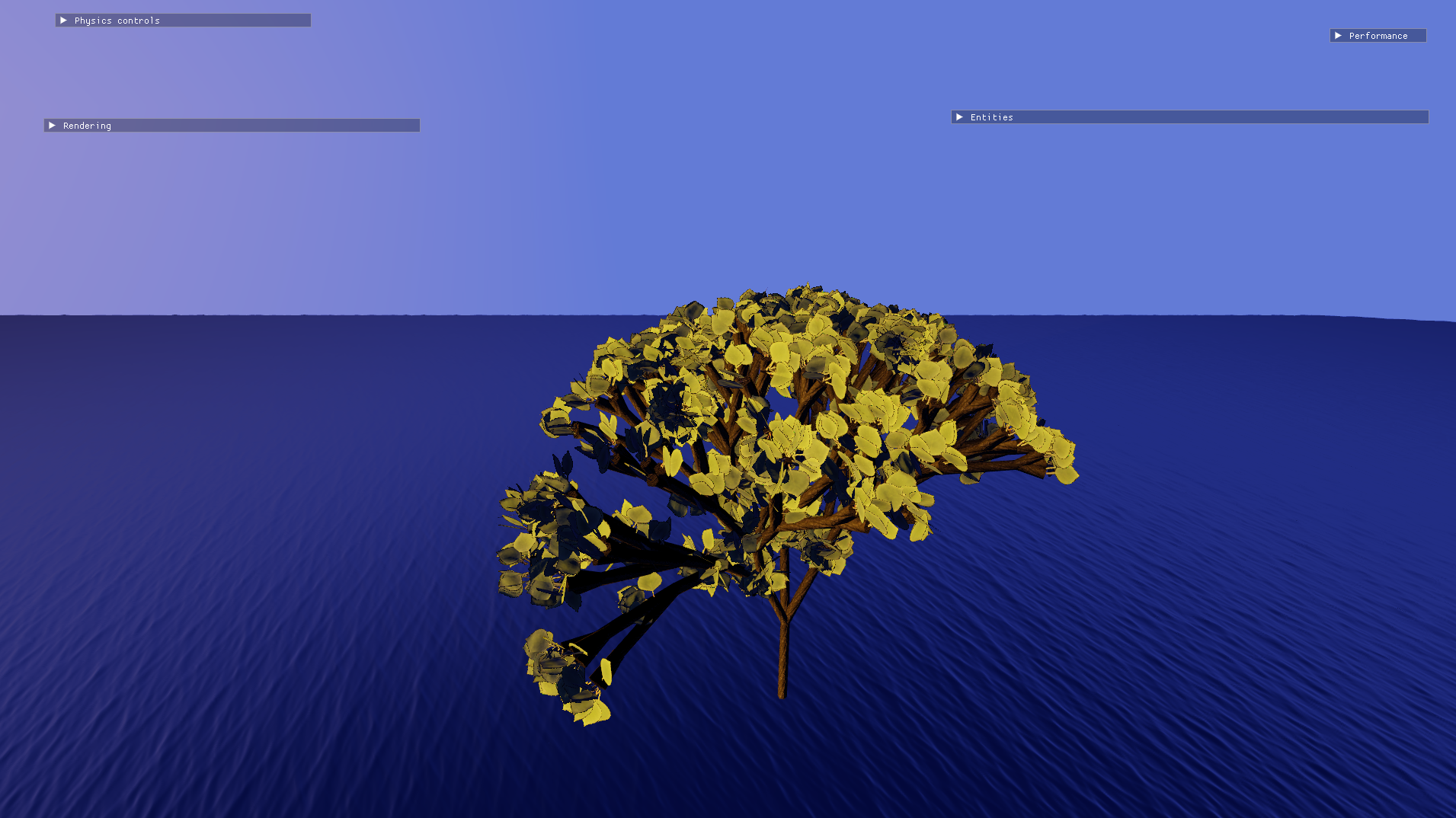

A tree branch

The next task was to combine these two together. At first, I naively transformed the vertices of the branch by the attachment transforms of the tree and added them to the same mesh. This took the vertex count up to more than 65,535, which meant I couldn’t use 16-bit indices. I decided to draw the branches using instancing as well so that I could keep using 16-bit indices and save on some memory usage and bandwidth. The attachment points of the branch were combined into the tree by applying the transform of each tree attachment to put them in the tree’s local space.

After combining the branches with the tree

The fully assembled tree

Improving performance

The tree above is the final version of the L-systems I used. To begin with, the tree had more leaves and looked like this:

An early iteration of the tree

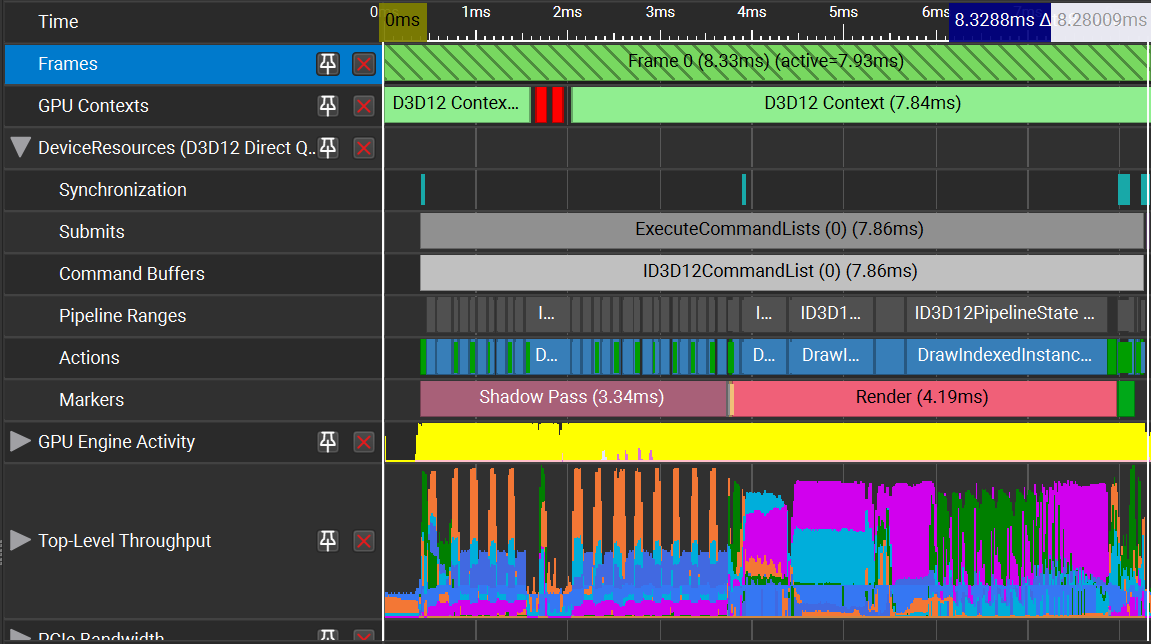

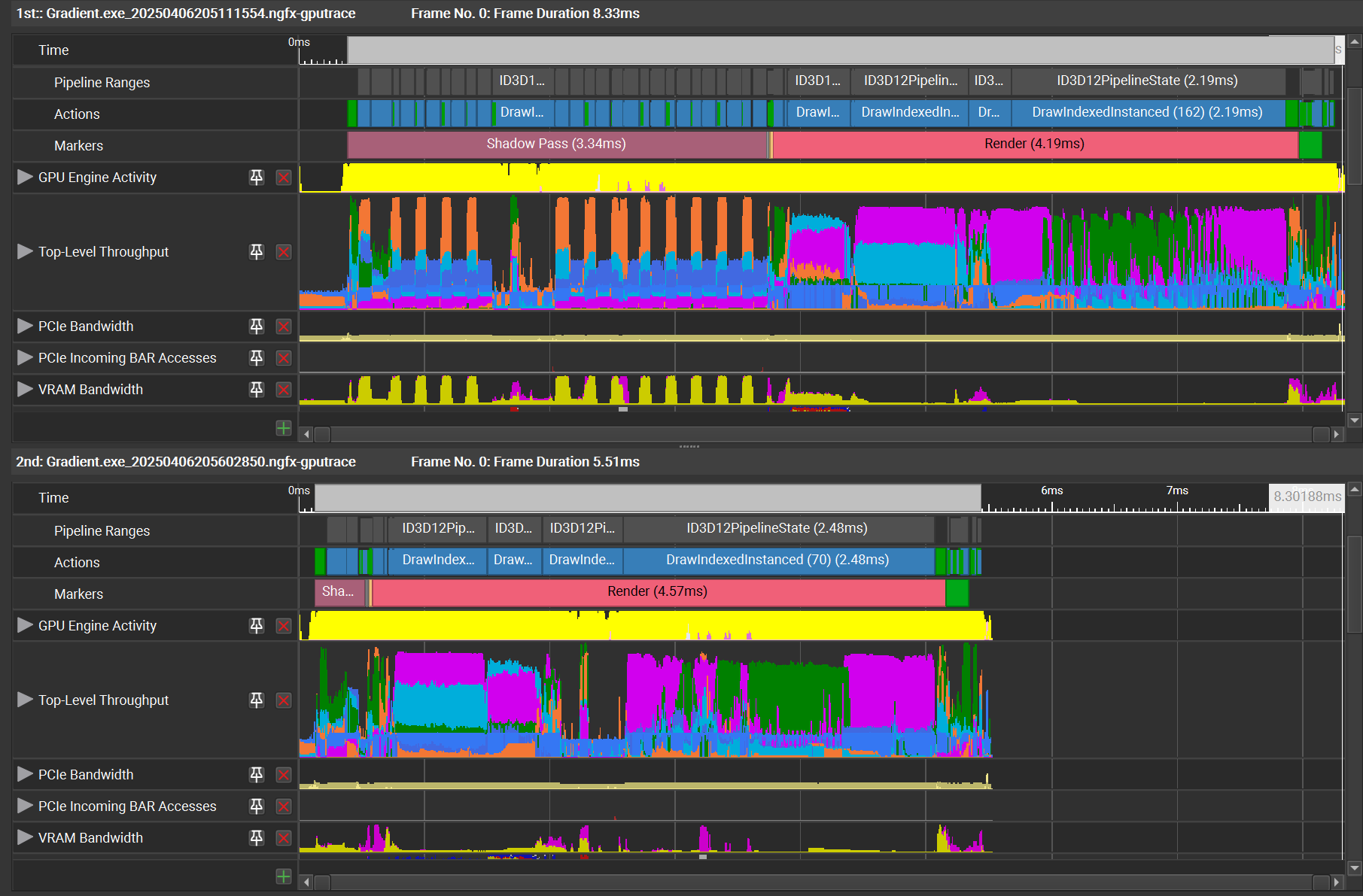

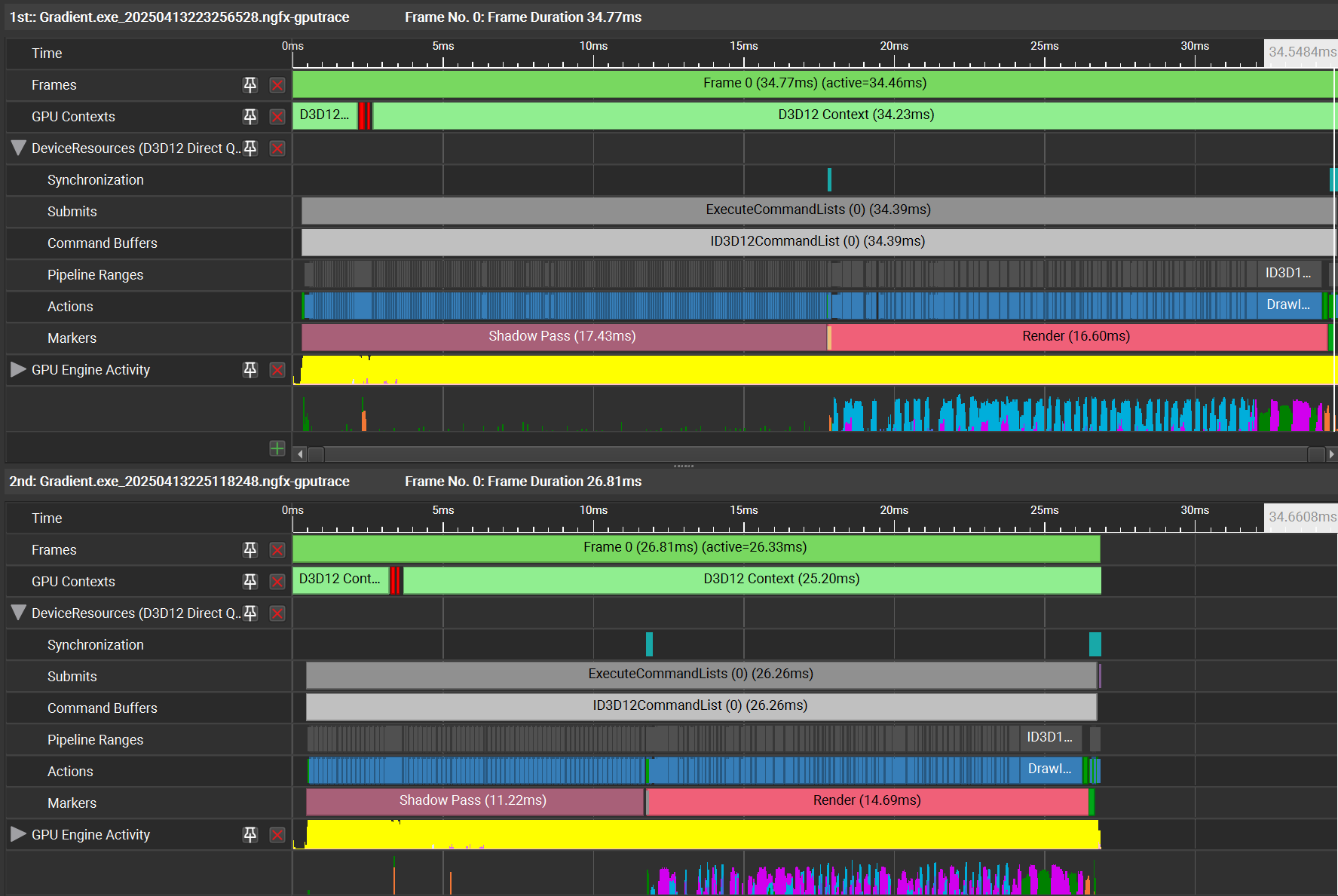

The performance here is quite poor - 6 msPF for just a single tree, and I was planning to have many more of these. I loaded up nSight Graphics to trace the application and see what I could do to improve performance.

Trace Analysis

nSight itself adds a lot of performance overhead so the absolute figures should be taken with a grain of salt, but the relative figures can still be helpful and instructive. Here, we can see that my shadow pass is taking an unusually long amount of time, almost as much as my main forward pass.

The frame timeline in nSight

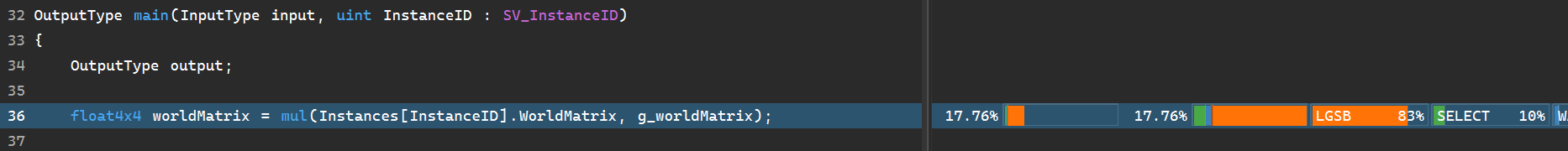

The largest hot spot according to nSight is in my instancing vertex shader, where we find a long scoreboard stall. This essentially means that the warp was stalled due to waiting for instance data to be read from the StructuredBuffer.

A long scoreboard stall

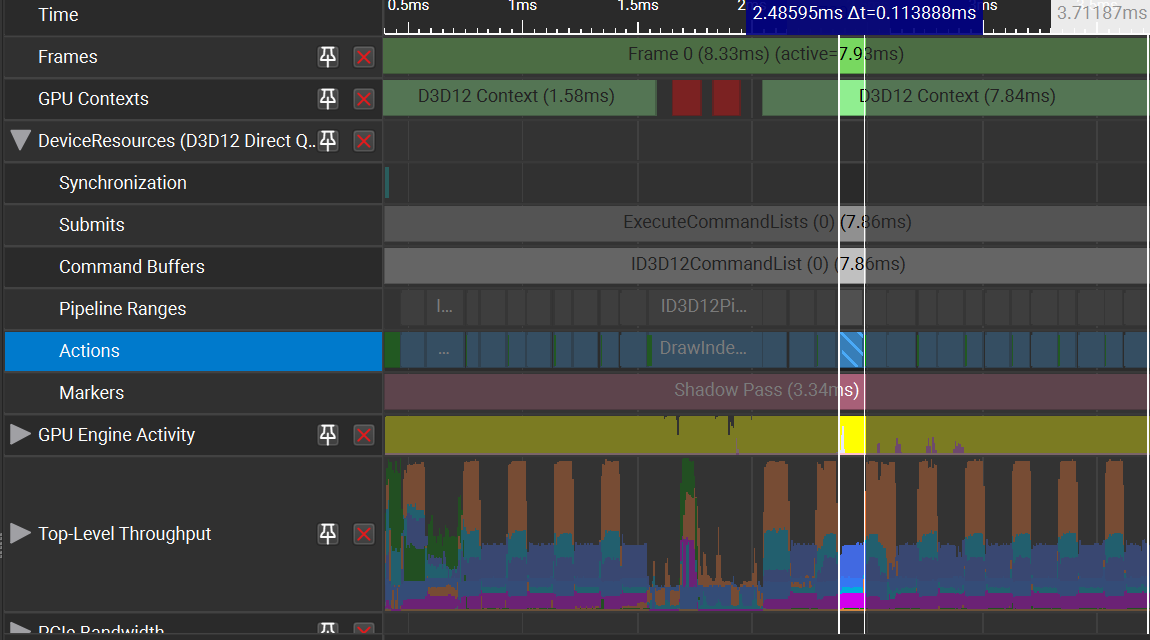

Zooming into the shadow pass, we see that the tree is being drawn many times over. The VRAM throughput spikes (orange) are due to the fact that I was still using a huge combined mesh with 32-bit indices for the trunk at this time.

The shadow pass

What can we conclude from this analysis? Somehow reducing the size of my StructuredBuffer could help with the long scoreboard stalls, but I think a better approach would be to reduce the amount of draw calls issued to begin with. In the shadow pass, the tree (leaves and all) are drawn once into the directional light’s shadow map. I also have two point lights in this scene, and each point light draws the entire scene 6 times(!) to write to its shadow map. The tree is drawn a total of 13 times for the sake of shadows. Surely we can do better.

Frustum culling

Frustum culling is the technique of discarding objects from a frame if they lie outside the camera’s view frustum, which is simply the visible space in front of the camera. In this case, it would obviously improve the frame time when not looking at the tree since it isn’t drawn, but frustum culling can also be applied when drawing the point light shadow maps. Point light shadows are drawn by placing the camera at the light, setting the far plane to the range of the point light and rendering depth in all six cardinal directions. With frustum culling, the tree would only be drawn in the light frusta that it intersects.

directxcollision.h has a number of bounding volume types, which I happily made use of. To implement frustum culling, I assigned an axis-aligned bounding box to most objects in my scene, including the various parts of the tree. The tree had one bounding box for the trunk and one bounding box each for the branches and leaves. In my render loop, I then performed an intersection test with the camera frustum for each object that had an AABB, and discarded it if it was outside the frustum.

I also started to draw the branches using instancing as well, which allowed me to use 16-bit indices for all meshes as mentioned above. I made a couple of minor tweaks in the vertex shader, and added some early returns in the pixel shader. I also passed the meshes through meshoptimizer to get rid of duplicate vertices and improve memory access. All these changes together resulted in a huge improvement in the frame time:

Much faster now!

In release mode without nSight running, the frame time went down to around 3.65 msPF (274fps) in a similar viewing position as above. The majority of the improvements came from the frustum culling, however - the shader tweaks and the mesh optimization appeared to be quite marginal in this case.

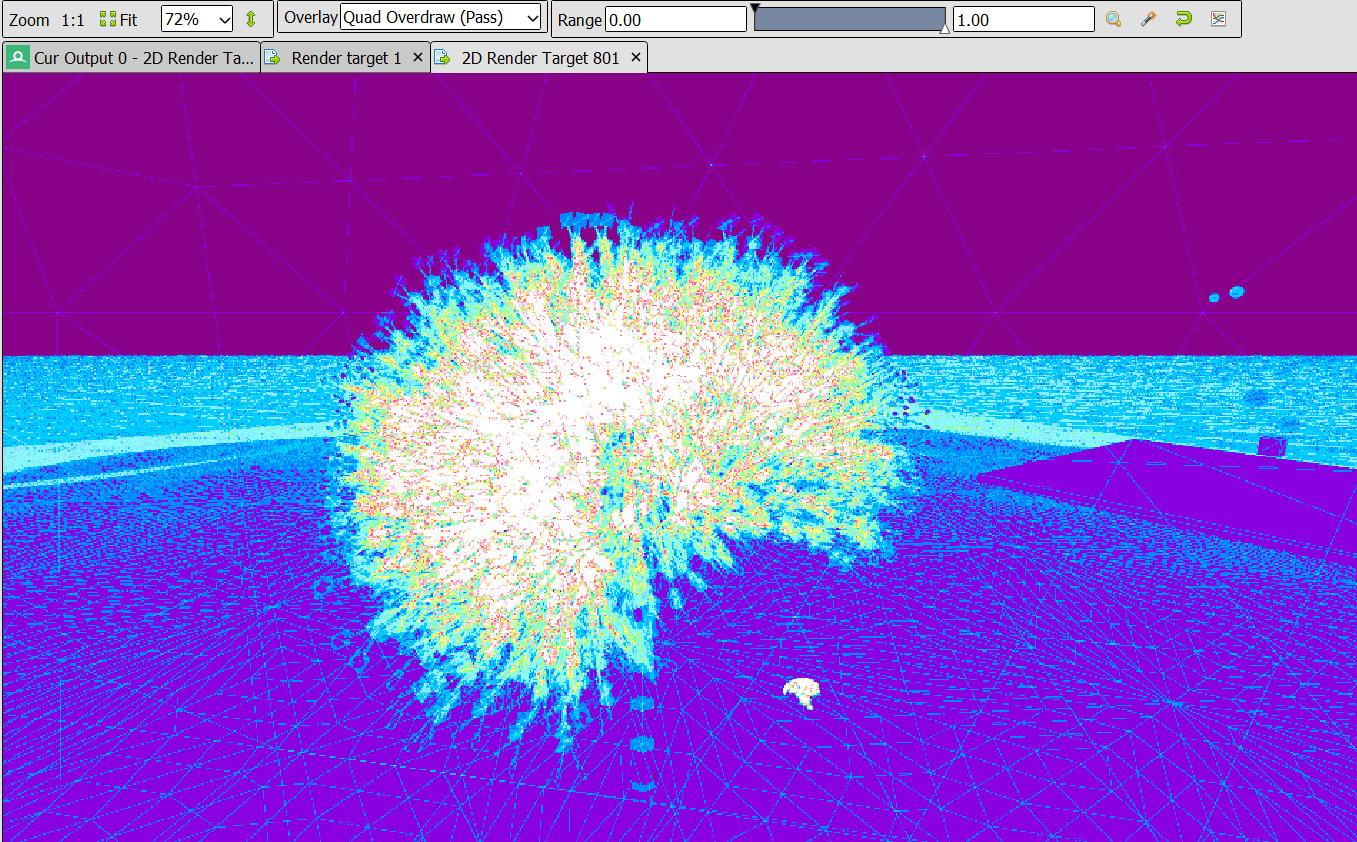

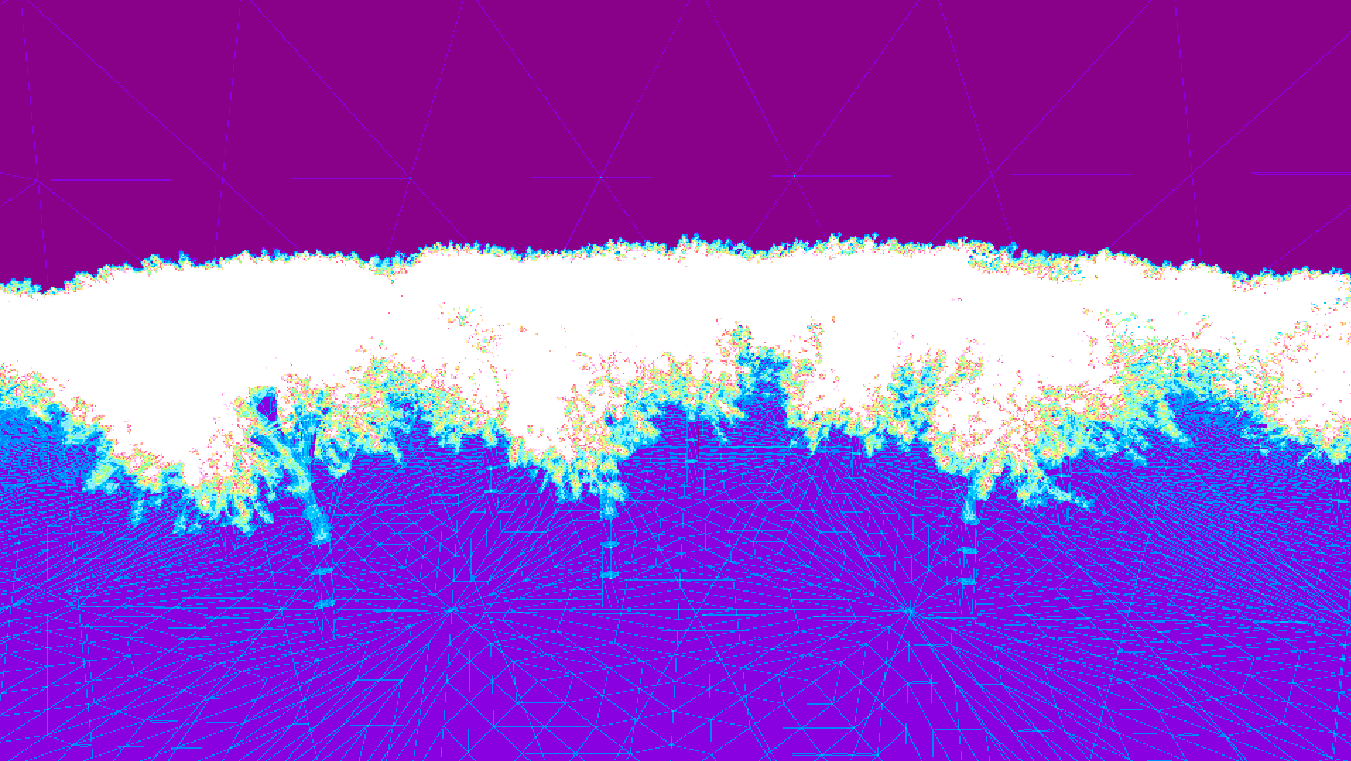

The obvious elephant in the room here is the time consumed in the forward Render pass. I believe this is due to huge amounts of overdraw caused by the branches and leaves:

Overdraw, visualized using RenderDoc

I’ll touch upon potential solutions to this later in the post. For the time being, I wanted to move on to rendering an entire forest.

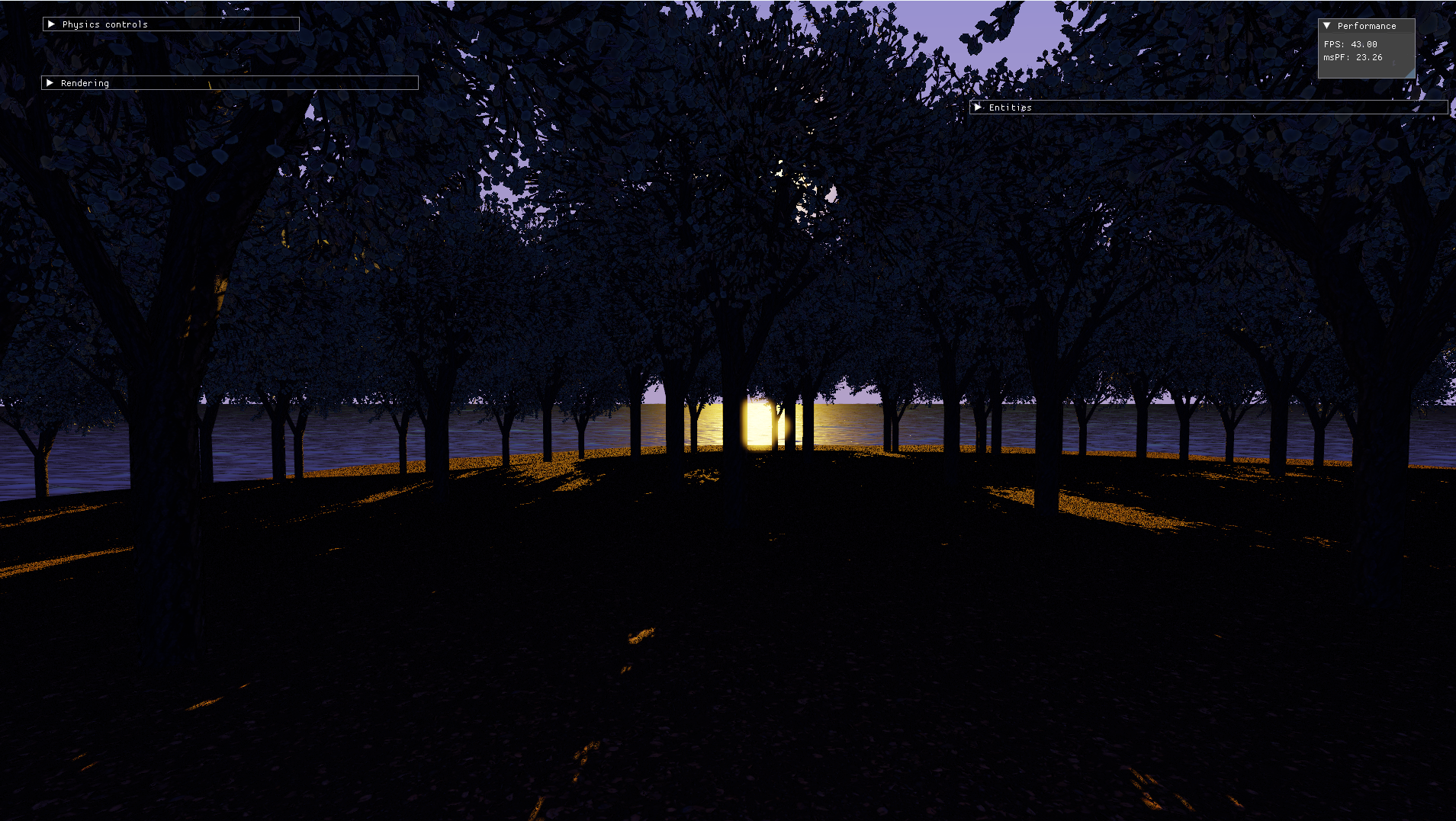

Drawing a forest

The tree above had 63,000 leaves. I tweaked the branch L-system to cut the number of leaves down to 30,600 as in the first tree picture above, which still looked pretty good. I decided to remove the point lights from the scene for the time being - I’ll find a way to reintroduce them later. I sprinkled a number of trees around my terrain using Poisson-disc sampling, and…

That’s a stunning shot, as long as you don’t look in the top right

What gives this time? I captured another trace, and found that the shadow pass was time-consuming again. This time it was the directional light shadows taking up all the time. My shadow map is large enough to fit the entire scene, which means that every tree (all 101 of them!) was being rendered to this shadow map.

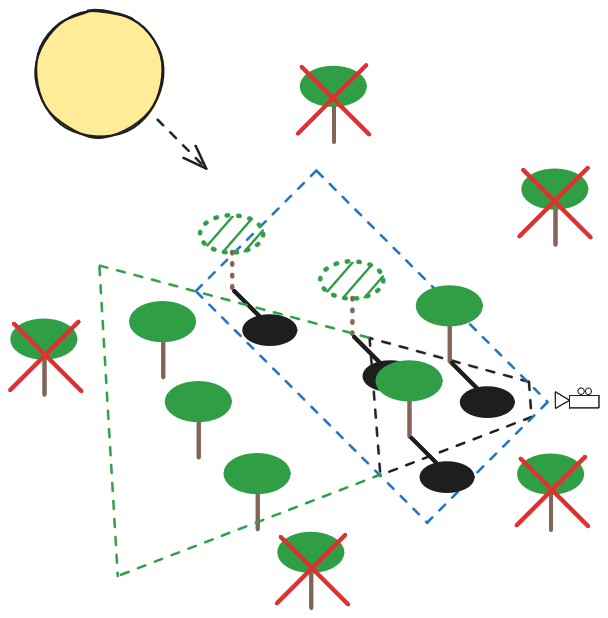

Culling with directional light shadows

The directional light frustum doesn’t need to be as large as the scene - it can be fit to the view frustum, as described here. Visually, this has the benefit of making efficient use of the resolution of the shadow map, and in my case, it also means I can use the reduced orthographic projection volume as a bounding box for culling!

The final culling system

Here, anything within the viewing frustum (green + black) will be drawn in the forward pass. Only objects within the light frustum (blue) will have their shadows drawn. Objects that are in the light frustum but not the view frustum will only have their shadows drawn, and anything outside both these frusta is culled completely. The light frustum is fit tightly around the camera’s shadow viewing frustum (black).

Note that the near plane cannot be tightly fit and must be placed at the bounds of the scene, or close to the light. This is because objects can potentially cast shadows into the view frustum from outside.

The shadow draw distance set to 10 for demonstration

My far plane is quite distant by default in order to be able to draw all the water, so I decided to use a separate draw distance for shadows. I set this draw distance to a little under half the width of the island.

Fitting the light frustum tightly caused a shimmering artifact to appear at the edges of the shadows. This occurs because the dimensions of the orthographic projection box change as the camera moves.

Shimmering artifacts at shadow edges

I tried the solution recommended here, which is to round the projection bounds to texel-size increments, but this didn’t work out for me. I’ve probably misunderstood something, but I decided to just enable my large kernel PCF for the time being. This softens the edges of the shadows and filters out the high-frequency shimmering, making it less obvious.

PCF papers over the shimmering

I’d like to use a lower shadow map resolution to save on memory and soften the shadow edges further, but lowering the resolution worsens the shimmering artifacts. I’ll try to look into this when I have the time, and I’m open to suggestions for a fix.

Results

Light frustum culling: before vs after

These frustum culling techniques improved the performance noticeably, especially towards the edges of the forest when not many trees are in sight. Without any sort of frustum culling, the engine would likely be stuttering along at under 10fps in the middle of the forest.

There’s still much optimization to be done, though. Drawing the tree and leaf geometry is still taking too long for my liking, and I could probably improve this by reducing the size of the instance data buffer. The transform for each instance is currently a 4x4 matrix of floats, which uses up a lot of memory. Since I’m not scaling the instances, I could replace this matrix with a position vector (4 floats, including 1 float for padding) and a quaternion representing the rotation (another 4 floats). This would bring the size of a single instance down to 48 bytes from 80 bytes, which should make more of the data fit in the GPU’s caches and thus improve access times. I’d also have the opportunity to animate the leaves in my vertex shader since I’d have access to the position and rotation separately.

The branches probably have many more triangles than necessary, and this is due to my somewhat naive tessellation when interpreting the L-system. I could address this in my code, but I wonder if I could use meshoptimizer’s simplification to cut down on the triangle count for me.

Yikes…

The overdraw from the leaves and branches is now the biggest performance hog. Since my renderer does not necessarily draw objects from front to back, the pixel shader is shading a piece of geometry only to have it overwritten later by another piece of geometry, leading to a lot of wasted work. To cut down on overdraw, I’ll have to modify my vanilla forward rendering pipeline into something more advanced like a deferred renderer, or introduce a Z-prepass.

There’s many artistic changes to be made also. I could add some more varieties of trees using my L-systems and sprinkle bushes about the place. Some props such as rocks would also make the environment look less plain. I’ll present these improvements in a follow-up post.

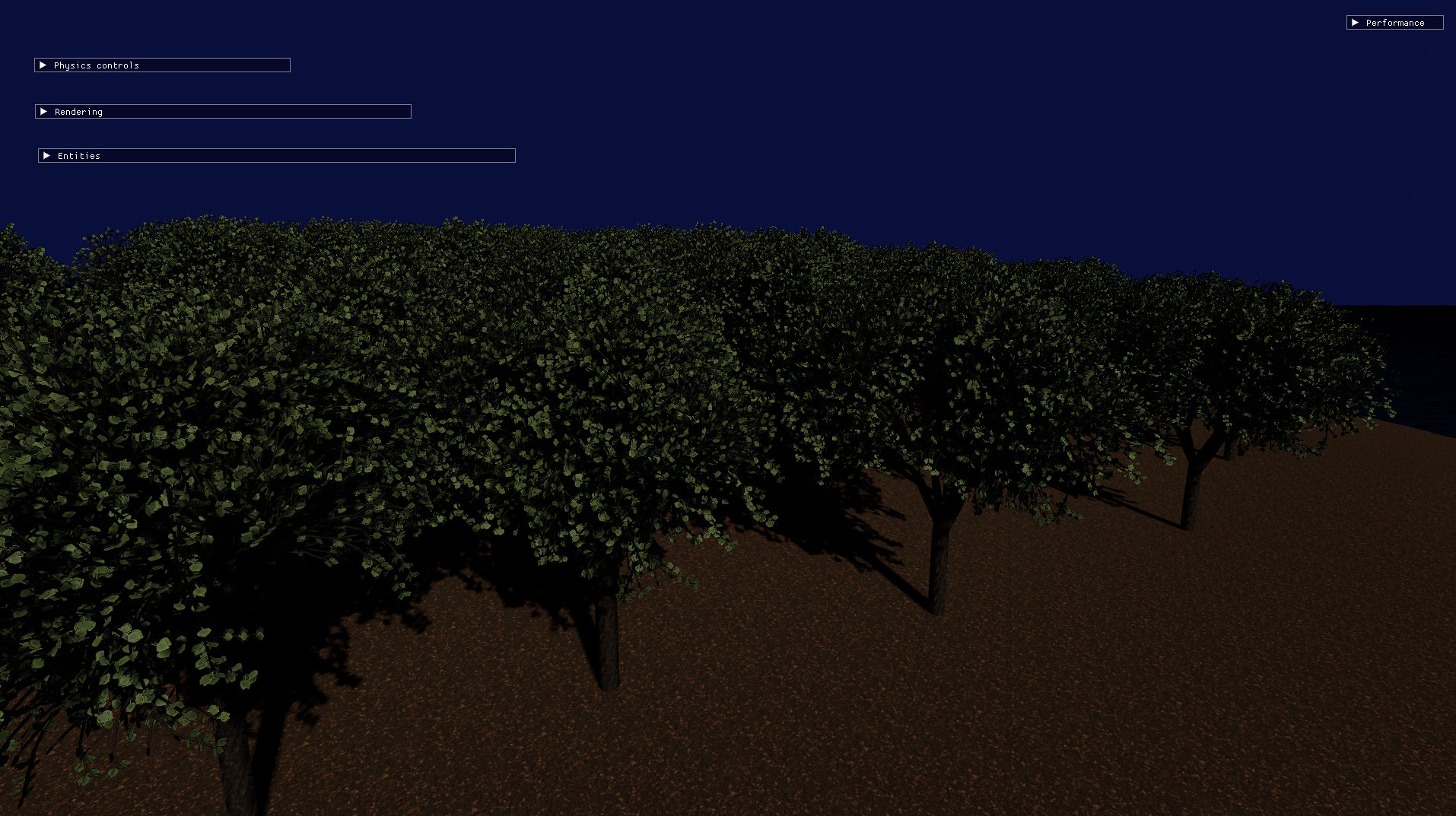

One last shot of the forest with nighttime lighting